Wabi-sabi, Marcel Duchamp and Zen

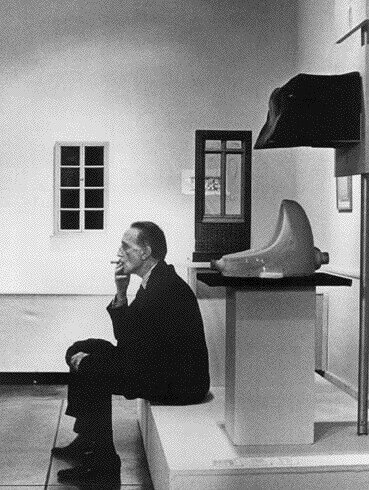

I gave November’s Dharma Bundle the title, ‘A Profoundly Ordinary Beauty - Wabi-sabi, Marcel Duchamp and Zen’. As usual it started with a single idea:

Was there a connection between Duchamp placing his urinal, and other ‘readymades’, into art galleries in the early 1900s and Rikyu, a few hundred years earlier, bringing rough, anonymous, utensils into the Japanese tea ceremony and creating a wabi-sabi aesthetic in the elite world of ‘tea’?

I was working on a hunch as I knew next to nothing about Duchamp. I think it was a good hunch, the more I investigated the more Duchamp’s insights came to light. I thought I’d share some of what I found here, they are taken from an interview with Pierre Cabanne in 1971.

LETTING GO OF SELF-VIEW

Cabanne: One has the impression that every time you commit yourself to a position, you attenuate it by irony or sarcasm.

Duchamp: I always do. Because I don’t believe in positions.

Cabanne: But what do you believe in?

Duchamp: Nothing, of course! The word “belief” is another error. It’s like the word “judgement”, they’re both horrible ideas, on which the world is based.

Cabanne: Nevertheless you believe in yourself?

Duchamp: No.

Cabanne: Not even that.

Duchamp: I don’t believe in the word “being.” The idea of being is a human invention.

Cabanne: You like words so much?

Duchamp: Oh yes, poetic words.

Cabanne: “Being” is very poetic.

Duchamp: No, not at all. It’s an essential concept, which doesn’t exist at all in reality, and which I don’t believe in, though people, in general, have a cast-iron belief in it. No one ever thinks of not believing in “I am”, no?

Duchamp does not believe in ‘positions’. He doesn’t hold to any view, to any belief. It’s as if he ‘rejects’ everything but the ‘real world’, directly experienced.

The poet Wallace Stevens saw the world as ‘shot through with conceptual content’. To be ‘shot through’ means to be intertwined with something, to be infused by some quality. It seems that Duchamp sees the world this way too, intertwined with, infused by, concepts.

Duchamp is often talked of as the first conceptual artist and the Tate defines conceptual art as art for which the idea (or concept) behind the work is more important than the finished art object.

But in exploring Duchamp what strikes me is that his work doesn’t idealise the conceptual, so much as expose it. He’s exposing the conceptual nature of much of our experience, the unreality of it.

His works show us, through our own reactions, what we make of things. The same is said of Wallace Stevens, he shows us that ‘things are what they are through an act of the mind’.

Self-view, sakkāya diṭṭhi, is sometimes referred to as ‘the mother of all views’. The view that there is some kind of separate, permanent, ‘self’ that we have or are, which is separate from the lived, moment to moment, experience.

Our experience is ‘shot through’ with the concept of ‘me’.

Reading his words I wonder if Duchamp had seen through this view? He says ‘No one ever thinks of not believing in “I am”, no?’

LETTING GO OF IDENTIFICATION

Cabanne: You’ve just returned from London where at the Tate (1966) an important retrospective of your work took place. I thought that exhibitions were “historic demonstrations” which you didn’t approve of?

Duchamp: But they always are! You’re on stage, you show off your goods; right then you become an actor… You have to be present at the opening; you’re congratulated, it’s so hammy!

Cabanne: You’re very graceful now about accepting this hamminess, which you’ve avoided all your life.

Duchamp: One changes. One accepts everything, while laughing just the same. You don’t have to give in too much. You accept to please other people, more than yourself. It’s sort of politeness, until the day when it becomes a very important tribute. If it’s sincere, that is.

Cabanne: What impression did the retrospective at the Tate Gallery make on you?

Duchamp: An excellent one. When your memory’s warmed up you see better. You go through it chronologically; the man’s really dead, with his life behind him. It’s a little like that, except I’m not dying! Each thing brought up a memory. And I wasn’t at all embarrassed by the things I didn’t like, that I was ashamed of, that I would have wanted to keep out. It was simply being laid bare, kindly, with no bruises, no regrets. It’s quite agreeable.

One sign that the first fetter, the fetter of ‘self-view’, is no longer operating is that we cease to identify with experience. Note; not that we cease to experience, not even that our experience is very different, just that we cease to identify with it. Another way of describing this ‘self-view’, maybe less abstractly, is as ‘the habit of identifying’, this is me, this is mine.

The loosening of that habit of identification is tremendously freeing. I feel this freedom in the way Duchamp, as an older man, looks back on his life and work.

He’s able to laugh at himself, he laughs at the idea of his own importance. He says, ‘I wasn’t at all embarrassed by the things I didn’t like.’ When we no longer identify, then the past is not an embarrassment to us, we no longer take it all so personally.

Instead, it’s all viewed with a tender kindness, ‘simply being laid bare, kindly, with no bruises, no regrets.’

LETTING GO OF HABIT

Cabanne: You’ve said, “when an artist brings me something new, I all but burst with gratitude.” What do you think the “new” is?

Duchamp: I haven’t seen so much of it. If someone brings me something extremely new, I’d be the first to want to understand it. But my past makes it hard for me to look at something, or to be tempted to look at something: one stores up in oneself such a language of tastes, good or bad, that when one looks at something, if that something is isn’t an echo of yourself, then you do not even look at it. But I try anyway. I’ve always tried to leave my old baggage behind, at least when I look at a so-called new thing.

When we meet a work by Duchamp what is exposed in us is everything that we bring to that meeting. Often we believe in an objective world out there that is ‘received’, by us, just as it is. But the dharma shows us how intimately our own perception is involved in creating that world.

In Buddhism, ‘what we bring’ is known as our samskaras. They include everything we bring to that particular moment. All our conditioning, everything that has happened to us, all our likes and dislikes and our moral hierarchies.

Duchamp sees this. He wants to open himself to the new but sees the inescapable baggage of his past, of his own samskaras. As David Hockney says, "We only see with memory. Everyone sees differently. We're all on our own.”

LETTING GO OF CONVENTIONS

Cabanne: How do you see the evolution of art?

Duchamp: I don’t see it because I doubt it’s value deep down. Man invented art, it wouldn’t exist without him. All of man’s creations aren’t valuable. Art has no biological source. It’s addressed to a taste.

Cabanne: It isn’t a necessity, in your eyes?

Duchamp: People who talk about art have turned it into something functional by saying, “man needs art to refresh himself”.

Cabanne: But there isn’t any society without art?

Duchamp: There isn’t any society without art because those who look at it say so. I’m sure that the people who made wooden spoons in the Congo, which we admire so much in the Musée de l’Homme, do not make them so they can be admired by the Congolese.

Cabanne: No, but at the same time they make fetishes, masks…

Duchamp: Yes, but these fetishes were essentially religious. It is we who have given the name ‘art’ to religious things; the word itself doesn’t exist among primitives. We have created it in thinking about ourselves, about our own satisfaction. We created it for our sole and unique use; it’s a little like masturbation. I don’t believe in the essential aspect of art.

He doesn’t believe in ‘art’ as something that essentially exists. He recognises it as a convention. We, as a society, have decided these things have value and these other things don’t.

To expose the absurdity of ‘art’ he takes a urinal and places it in the art gallery. What is it?

He’s created this cognitive dissonance. The urinal lying there, on its back, in the gallery is no longer ‘plumbing’, but it’s not ‘art’ either, because it’s a urinal!

He famously says, ‘I don’t believe in art, I believe in artists.’

I wonder how this principle translates from art practice into dharma practice?

For him, the artist uses the object as a pointer. It’s not then so much an object but an action. An action designed to show us something about ourselves. If we then ‘enshrine’ the object itself we’ve missed the point entirely.

It like ‘the finger pointing to the moon’, if you concentrate on the finger you’ll miss the moon.

RESTING ON DIRECT EXPERIENCE

Duchamp: Metaphysics is a tautology; religion is a tautology: everything is a tautology, except black coffee because the senses are in control! The eyes see the black coffee, the senses are in control, it’s a truth; but the rest is always tautology.

Everything is a tautology, everything is a needless repetition of ideas, most is redundant. In a world that he sees as, ‘shot through with conceptual content', he rests on ‘direct experience.

That’s what he comes back to, that’s what he trusts, the sight of the black coffee, the smell, the taste, the heat of the black coffee.

Black coffee is real.